History

The gravitational weakening of light from high-gravity stars was predicted by John Michell in 1783 and Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1796, using Isaac Newton's concept of light corpuscles (see: emission theory) and who predicted that some stars would have a gravity so strong that light would not be able to escape. The effect of gravity on light was then explored by Johann Georg von Soldner (1801), who calculated the amount of deflection of a light ray by the sun, arriving at the Newtonian answer which is half the value predicted by general relativity. All of this early work assumed that light could slow down and fall, which was inconsistent with the modern understanding of light waves.

Once it became accepted that light is an electromagnetic wave, it was clear that the frequency of light should not change from place to place, since waves from a source with a fixed frequency keep the same frequency everywhere. One way around this conclusion would be if time itself was altered—if clocks at different points had different rates.

This was precisely Einstein's conclusion in 1911. He considered an accelerating box, and noted that according to the special theory of relativity, the clock rate at the bottom of the box was slower than the clock rate at the top. Nowadays, this can be easily shown in accelerated coordinates. The metric tensor in units where the speed of light is one is:

and for an observer at a constant value of r, the rate at which a clock ticks, R(r), is the square root of the time coefficient, R(r)=r. The acceleration at position r is equal to the curvature of the hyperbola at fixed r, and like the curvature of the nested circles in polar coordinates, it is equal to 1/r.

So at a fixed value of g, the fractional rate of change of the clock-rate, the percentage change in the ticking at the top of an accelerating box vs at the bottom, is:

The rate is faster at larger values of R, away from the apparent direction of acceleration. The rate is zero at r=0, which is the location of the acceleration horizon.

Using the principle of equivalence, Einstein concluded that the same thing holds in any gravitational field, that the rate of clocks R at different heights was altered according to the gravitational field g. When g is slowly varying, it gives the fractional rate of change of the ticking rate. If the ticking rate is everywhere almost this same, the fractional rate of change is the same as the absolute rate of change, so that:

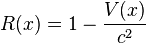

Since the rate of clocks and the gravitational potential have the same derivative, they are the same up to a constant. The constant is chosen to make the clock rate at infinity equal to 1. Since the gravitational potential is zero at infinity:

where the speed of light has been restored to make the gravitational potential dimensionless.

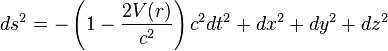

The coefficient of the in the metric tensor is the square of the clock rate, which for small values of the potential is given by keeping only the linear term:

and the full metric tensor is:

where again the c's have been restored. This expression is correct in the full theory of general relativity, to lowest order in the gravitational field, and ignoring the variation of the space-space and space-time components of the metric tensor, which only affect fast moving objects.

Using this approximation, Einstein reproduced the incorrect Newtonian value for the deflection of light in 1909. But since a light beam is a fast moving object, the space-space components contribute too. After constructing the full theory of general relativity in 1916, Einstein solved for the space-space components in a post-Newtonian approximation, and calculated the correct amount of light deflection – double the Newtonian value. Einstein's prediction was confirmed by many experiments, starting with Arthur Eddington's 1919 solar eclipse expedition.

The changing rates of clocks allowed Einstein to conclude that light waves change frequency as they move, and the frequency/energy relationship for photons allowed him to see that this was best interpreted as the effect of the gravitational field on the mass–energy of the photon. To calculate the changes in frequency in a nearly static gravitational field, only the time component of the metric tensor is important, and the lowest order approximation is accurate enough for ordinary stars and planets, which are much bigger than their Schwartzschild radius.

Read more about this topic: Gravitational Redshift

Famous quotes containing the word history:

“I feel as tall as you.”

—Ellis Meredith, U.S. suffragist. As quoted in History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 4, ch. 14, by Susan B. Anthony and Ida Husted Harper (1902)

“When the coherence of the parts of a stone, or even that composition of parts which renders it extended; when these familiar objects, I say, are so inexplicable, and contain circumstances so repugnant and contradictory; with what assurance can we decide concerning the origin of worlds, or trace their history from eternity to eternity?”

—David Hume (1711–1776)

“The history of any nation follows an undulatory course. In the trough of the wave we find more or less complete anarchy; but the crest is not more or less complete Utopia, but only, at best, a tolerably humane, partially free and fairly just society that invariably carries within itself the seeds of its own decadence.”

—Aldous Huxley (1894–1963)